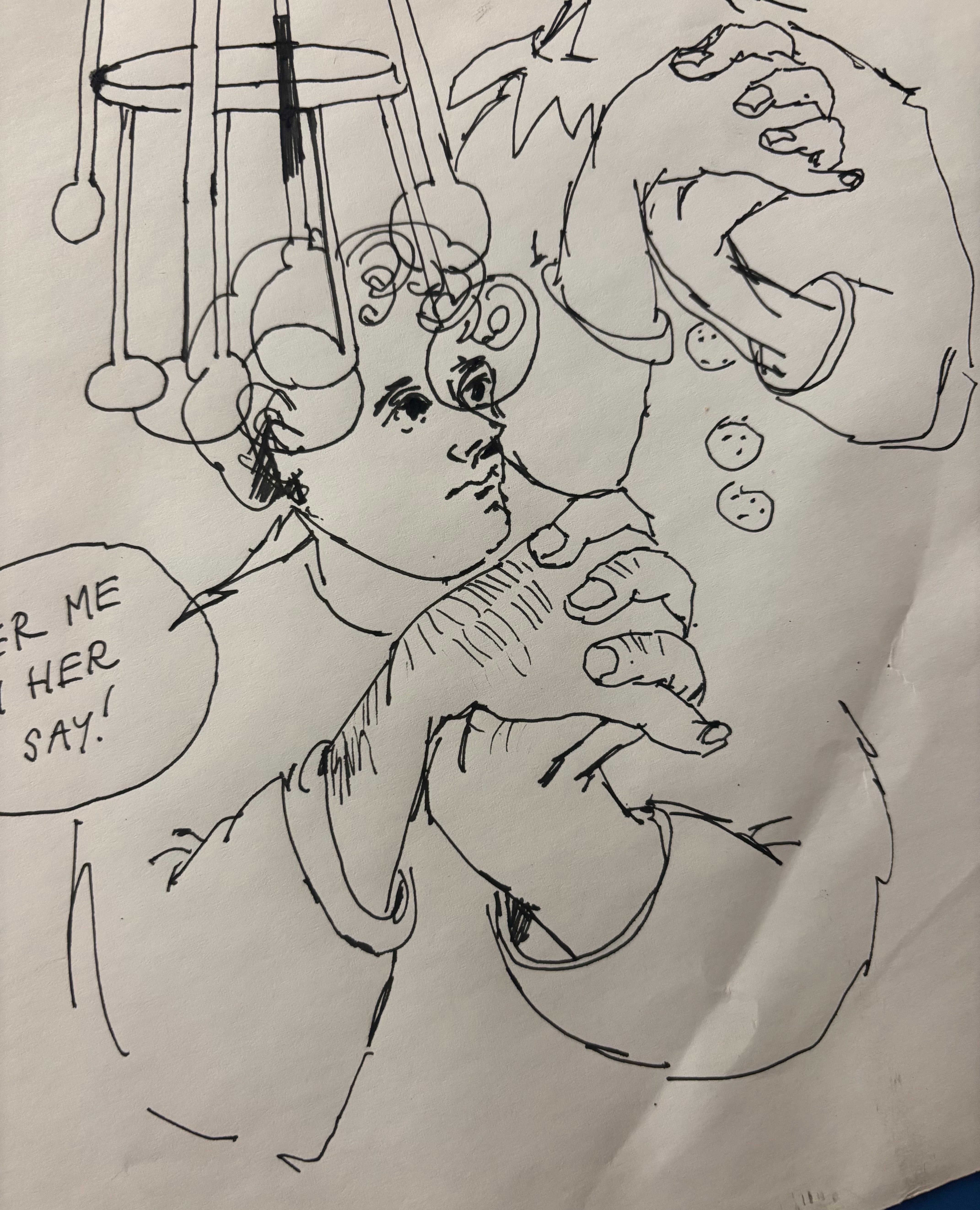

A few days ago I was scrolling through Instagram and I saw a screenshot from a Looney Tunes episode called “Bowery Bugs.” In the screenshot was the Brooklyn Bridge in 1886 in cartoon. It felt like an anachronism. Interested, I looked it up and watched the 7 minute short about a man down on his luck who craves the magic of a rabbit foot. Of course the rabbit foot he wants is Bugs Bunny’s, who uses his cunning trickery to convince the man to use other kinds of luck omens instead of the one that requires Bugs be amputated and adorned with a gold chain. The episode was funny if not a little boring but I was struck by one frame and have not been able to stop thinking about (and drawing) it since. It’s of the man as he dreams of the physical embodiment of his changing luck, the rabbit’s foot. Upon thinking of the foot, his large hairy hands clasp each other in pure adoration for his fruitful future. I loved how they bow in their weight, how the strange anatomy of the mans face is on full display, how he dips the tip of his sausage pinky with an unexpected elegance.

This Looney Tune frame made me think of the importance of hands in a drawing. I often draw them first, before the head or body, just the hands on their own. This often means my scale is all messed up when I do eventually draw the rest of the figure, but I don’t mind. I love when hands are the vacuum for someones entire being. When they themselves can have dreams of a luckier tomorrow.

On Friday I gave my friend a tattoo of a bird with a twig in its mouth. It went right above the crease on the other side of the elbow which paralleled nicely with a tattoo positioned similarly on their other arm. I can tell my skills are improving because starting a new tattoo doesn’t feel like a risk for the reward anymore. That I might mess someone up permanently. Now it feels more like the freedom I get from drawing.

I’ve been feeling like my drawings are leaning too heavily on being an image or are too readable or understood as a story. Figures – animals and humans – seem like a constant presence and with them seeps the entire composition in a narrative quality that I didn’t necessarily aim for. I wanted to break out of that bind. Tension. Let abstraction take hold beforehand instead of as the afterthought. And so I took a brush too big for the format of my sketchbook and stood over the book, blindly sopped up old paint in a pallet and spreading it all over the page. I was left with an uncomfortably fuzzy and shapeless mess of colors and paints. Synthetic purple watercolor, rust-colored gouache, mustard gouache full of dusty particulates, bright red lipstick, a pan of fancy neon pink paint I got in London that I was once too scared to use because it felt finite. I made lunch and allowed the paper to dry completely. When I went back to work I hunkered down on the ground and traded the big brush for one smaller than I’d typically use. In the soft ground of color I searched for shapes and found lamps and lightbulbs and trophies and of course dogs but also a freedom of reason for how they interacted. A horizon line that coiled, atmosphere inconstant in its opacity. My process is usually one of honing on sense but here I was honing in on something I knew was senseless.